Eric Bonds, Associate Professor of Sociology at the University of Mary Washington

What would it look like for Fredericksburg to be advancing along the path towards the achievement of climate justice by 2030? This journey first begins when Fredericksburg leaders, city staff, and community volunteers recognize that our town, like cities and towns across the United States, is highly unequal and has been shaped by a history of racism. Taken together, this means that some residents may be harmed more by climate change than others, and may not equally benefit from the transition to renewable energy. For instance, Fredericksburg today has an incentive on the books for homeowners to reduce their property taxes by installing solar panels, which is wonderful. But this tax incentive isn’t accessible to the majority of Fredericksburg residents because most people who live here (about 65%) rent their homes. Additionally, 15.5% of city residents live below the official poverty threshold, while another 40% live above the poverty threshold but with an income barely sufficient to pay for basic necessities like housing, health insurance, and childcare. These residents, whom the United Way describes as Asset-Limited, Income-Constrained, and Employed (ALICE) have almost no surplus income to purchase “green” products like solar panels and electric cars.

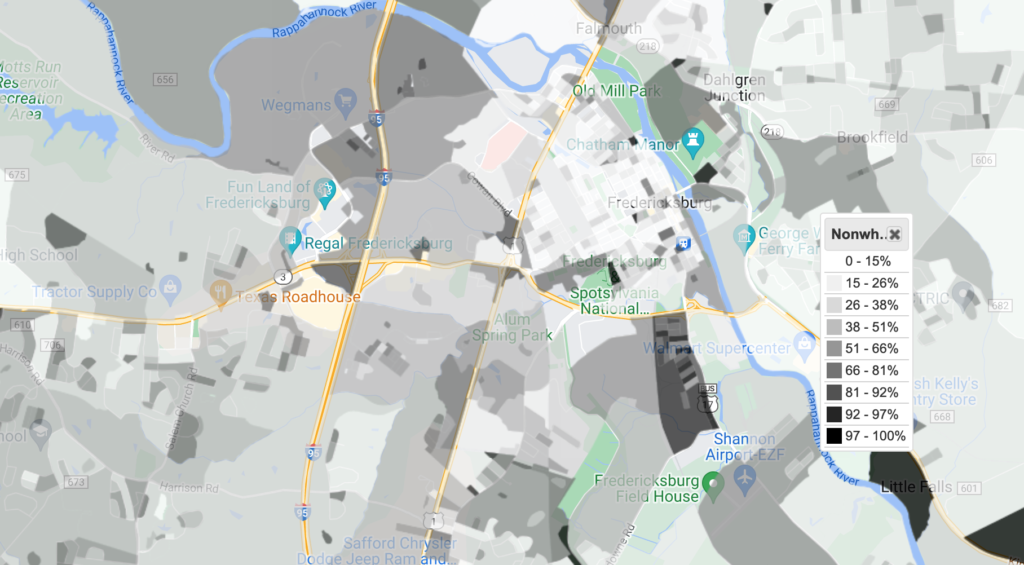

Additionally, a history of racism means that access to many environmental amenities in Fredericksburg like greenspaces, tree canopy, and opportunities for safe nonmotorized transportation may differ by race. Future amenities, like access to electric car-charging stations, could fall into the same pattern without care.

But it doesn’t have to be this way. The pathway imagined here shows how environmental decision-making might look if inequalities were taken into account, starting first with efforts to ensure that all members of our community are fully included in climate-change conversations.

Representation and Inclusion of Diverse Voices in Climate Planning

Fredericksburg leaders might begin by following the examples of communities like Providence, Rhode Island, which has already created a climate-planning process that centers on justice. Providence began its planning process by conducting a survey of residents in low-income neighborhoods in order to ask them about their experiences of the environment, including questions about home heating and cooling needs, access to nature, and environmental safety. Building on this, Fredericksburg could create a climate-planning committee that is reflective of Fredericksburg’s demographics, which must include people of color and residents in lower-income neighborhoods. In order to ensure that parents with children at home can attend meetings, the City of Fredericksburg could make childcare available for members of all its commissions. And because young people have the biggest stake in the future and our response to climate change, four seats of the climate-planning committee could be reserved for James Monroe and University of Mary Washington students.

Achieving Energy Justice

With a committee that includes residents from across the city of Fredericksburg, one representative of all of Fredericksburg’s diversity, the planning committee might hone in on the goal of achieving energy justice as an important component of climate justice. Doing so would ensure that a transition to renewable energy away from fossil fuels benefits all residents, and not just those with more wealth and income. Energy justice begins with a recognition that low and moderate income residents in Fredericksburg spend much more of their income on energy: in 2021 those living on incomes at 200% of the poverty level paid 9% of their income on energy, while those living at or below the poverty level spent 23% of their income to heat and cool their homes. In contrast, higher-earning residents of Fredericksbug spent only 2% of their income on energy.

In response, Fredericksburg leaders might make significant investments in energy efficiency and renewable energy for low and moderate income residents. First, they could follow Charlottesville’s lead by combining local funding with federal and state money to conduct energy audits across the city, and to then help weatherize the homes of low-income residents. Doing so could lead to both meaningful reductions in energy bills and a lower overall carbon footprint in the city. Second, community leaders might take inspiration from the Thurman Brisben Center’s decision to solarize its rooftop, resulting in a dramatic reduction in its energy cost. Building off the local homeless shelter’s success, in future years the city of Fredericksburg could set an ambitious goal—possibly tapping into philanthropic support and other funding—to bring solar panels to Hazel Hill and homes in other lower-income neighborhoods.

Investing in Transportation Justice

Beyond heating and cooling a home, transportation requires energy too. For this reason, the importance of public transportation is likely going to increase in a carbon-constrained world. Consequently, city officials could make important new investments in the Fred Transit system in future years. While this is something that would benefit all Fredericksburg residents, it would especially help those living on limited budgets. FREDTransit is already making big headway after securing a state grant that will allow residents to ride without paying bus fare. The city can further realize transportation justice by extending the city’s walking and bike path system to all areas of the city, ensuring that no one is cut off from this increasingly popular form of low-carbon recreation and transportation.

Mapping for Justice

While working to achieve energy and transportation justice, Fredericksburg leaders and community members can also conduct a full-scale inventory of their city to learn about where people enjoy the fewest environmental amenities, such as an extensive and healthy tree canopy, access to greenspace, and availability of electric vehicle charging stations. Fredericksburg officials should also ensure that low-income persons are not disproportionately located in flood zones, while developing a plan to ensure that disaster response to future storms is fully equitable. Rather than keeping this kind of assessment within City Hall, city officials could involve residents from across the community to participate and engage in a lively conversation about environmental equity as the city plans for the future.

Starting in 2022, Fredericksburg leaders can put their community on a path toward climate justice. In so doing, they can create a stronger, safer, and more pleasant town for us all. Looking back, by 2030, they will be able to feel an immense sense of pride.